Thuamul Rampur is in the Kalahandi district of Orissa. It is a tribal dominated area where the the land is predominantly undulating and hilly. The tribal population grow oil seeds, pulses, maize and ragi, etc on the hilly upland (bhatta land) and develop the streambeds on low lands (bahal land) for paddy crop. 67% of ANTODAYA’s target community is landless and they cultivate encroached government land.

Landlessness is defined in the State Land Reform Act as a person owning less than 1 standard acre of land. A standard acre being equivalent to:

- 1 acre of class I land (Irrigated land capable of producing more than 2 crops a year)

- 1.5 acres of class II land (Irrigated land capable of producing one crop a year)

- 3 acres of class III land (other than irrigated land where one crop of paddy can be grown in a year)

- 4.5 acres of class IV land (Any other land)

From its inception ANTODAYA has concentrated on ascertaining the people’s right over their natural resources especially land.

RESTORATION OF MORTGAGED LAND FROM MONEY LENDERS

Before ANTODAYA’s intervention in the area there were a large number of tribal land alienation cases. Despite Regulation 2 of Orissa Land Reforms Act 1956 prohibiting the sale or mortgaging of tribal lands to non-tribals in order to prevent land alienation, a large number of tribals were succumbing to selling or mortgaging their lands.

Two types of land mortgage are prevalent in the area namely katti bandha and kado bandha. In the case of katti bandha, the loanee makes an agreement with moneylender for a specific period of year for a specific amount. During this period the moneylender cultivates the land and the returns he gets from the land are taken as the repayment for the loan. At the end of the period the land automatically returns to its owner. Khatti bandha loans tend to be for small amounts and up to 3 acres of land is often mortgaged for four years in lieu of a loan of as little as Rs. 600/-. Katti bandha is used to for small consumption loans and is preferred over kado bandha as there is no need for an actual repayment in cash. However there are inherent disadvantages in katti bandha loans in terms of the loss of produce from the land which is taken in lieu of interest. In addition, there is no set pattern in relation to the amount loaned against a specific area. This depends entirely on the bargaining skill of the moneylender and/or the urgency of loan need in case of the potential loanee.

Finding that our target population were unaware of the laws relating to tribal land alienation, ANTODAYA started to educate the people by organising legal awareness camps and village level meetings. The issue of land alienation was so challenging and captivating that ANTODAYA was plunged into a fray against the moneylenders and land grabbers. It took almost 2 years to take up the issue of land alienation with the concerned authorities resulting in the District Administration coming forward to help the tribals in get back their land. A P.I.L. was also filed in the High court of Orissa which led to a Commission of Inquiry by Justice Baidyanath Mishra. The High court also advised the administration to allow tribals to plead without the services of advocates. As a result more than 175 acres of alienated lands were restored to the tribals. Before ANTODAYA’S intervention, there were 82 cases where people had mortgaged their land, now there are none.

ACQUISITION OF LAND FROM GOVERNMENT

After the restoration of tribal lands, ANTODAYA kept its commitment by helping people in their fight for survival. We organised the Legal Aid Camps which provided an interface between the revenue officials and the people at village level and helped to make tribal people aware about the existing laws relating to acquisition of both homestead as well as agricultural land through legal process and the type of land which could be acquired. We also tried expand the asset base of landless tribals through land reclamation and wasteland development for agriculture and we also encouraged the people to place their cases before the revenue officials and file applications for their encroached lands in order to obtain Record of Rights (Patta) for both homestead as well as arable land.

ACQUIRING REVENUE STATUS

There were 5 villages in the district area (Semelpadar, Tentulipadar, Ushamaska, Sorishbundel and Kirkicha) which were not declared as Revenue Villages until July 2002. All the lands in those unsurveyed villages remained in the hands of the government and, because the people didn’t have legal rights over the land, they identified as “encroachers”. As a result, they were harassed by both Forest and Revenue Department officials and every year they were made to attend court and pay fines. In addition, without revenue status, services like school, drinking water facilities, anganwadi and other social security services, employment generation opportunities and even wage employment simply didn’t reach them. Piri Majhi of Semelpadar village described the people of his village are deprived of Indira Awas Yojana (IAY) houses, as they didn’t have patta land. With a view to ensure peoples right over the land, ANTODAYA adopted some diplomatic processes in these unsurveyed villages. It highlighted the issue in the media and made contact with other departments like DPEP, ITDA and the Block Office and established schools, grain banks, roads etc in those villages. We also contacted banks and the block office and obtained loans (through SGSY and other schemes) as well as old-age pensions etc. We sanctioned and guided people to file applications before the government using the existing declarations and paper clippings with the recommendations of the local Sarpanch who collected the documents such as penalty receipts, loan receipts, LAMPCS membership slips and other proof of residence and organised a letter campaign. These actions helped the people to get the village MLP passed at the Gram Sabha which in turn mobilised infrastructure projects for example schools, grain banks, houses and dDrinking water facilities. By using a Target Push approach,the officials of the RWSS, ITDA, banks and welfare department as well as the DRDA, ANTODAYA encouraged people to develop land and pay fines to the revenue officials and in order to get proof in their name. After continuous effort from people as well as from ANTODAYA on 19th July 2002, Ushamaska, Sorishbundel and Kirkicha obtained Revenue status and people were granted patta. Unfortunately the other two villages (Semelpadar and Tentulipadar) were left out because they were in the roposed Karlapat Sanctuary area. However, the people of Orissa High Court has passed a stay order in favour of the villagers of Tentulipadar and forest officials are forbidden at present from evicting them.

FIGHTING EVICTION FROM FOREST LANDS

The Supreme Court of India has passed a judgement saying that the forest land is shrinking and have blamed this on the tribals who, they say, encroach forest lands for agricultural purposes and that they shoul d be evicted from their lands by the state Governments. This ruling has, in effect, become an appeal for state Governments to evict centuries old forest dwellers from their natural habitat and preparations have already been initiated in this direction. This is a basic issue of survival for the tribals as the forests are their natural habitat and their livelihood systems are intimately linked with it. The tribals of the project area joined together in large numbers at Karadapadar in 2002to demonstrate their solidarity and their combined wrath against this of Government policy. ANTODAYA organised the camp and facilitated participation of lawyers, concerned citizens and other civil society members. In addition, we organised a signature campaign of tribal people and sent them to the District Administration, the state government, the central government, the Chief Justice of India and the President of India. The tribals are determined not to leave their land and areready to face any sort of consequences.

AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION

ANTODAYA has taken up multi dimensional activities to enhance the arable land holdings, to level the undulated terrain for better crop production and to create tangible resource base for sustenance of the landless and marginal farmers. We have extended both financial as well as technical support to the landless people to acquire cultivable wastelands and then turn those into arable lands through land development activities. As a follow up measure ANTODAYA has helped people to reclaim those developed lands by liaisoning with Government. As an impact of this activity, the quantity of the arable land has increased at the village level, production has increased which helps people to ensure food security at the household level. Above all the sustained efforts from ANTODAYA have helped the people to gain control over the most tangible assets base for their sustenance.

Next Page >>

<< Previous

HARI MAJHI

Hari Majhi is about 13 years old and lives with his father and mother and two younger brothers in Lainguda Village under the Karlapat GP. In common with other people in the village, Hari’s father, Jaising Majhi, did not have a Record of Rights (ROR) for either homestead or arable land and depended slash and burn or shifting (podu) cultivation, daily wages and collection of forest produces for his livelihood. His family faced food scarcity for more than 6 months a year. During the podu cultivation season, Jaising used to take his Hari with him to the top of the hill and where he was told to protect the standing crop from the monkeys who used to pick the flowers and destroy the crops. Hari’s essential contribution to his family’s livelihood meant he did not have time to attend school or to study. During the preparation of micro-level plans for Lainguda village, ANTODAYA discovered that none of the 19 families in the village had Record of Rights (ROR) for either homestead or arable land and, in order to rectify the situation, ANTODAYA encouraged the people to encroach the cultivable wasteland and supported them financially to reclaim those lands for cultivation. We also encouraged the villagers to submit their application with the Revenue Department to get ROR and organised series of legal camps to discuss the rules,regulations and procedures involved for obtaining ROR. Ultimately in 2001, Jaising, alongwith other people of his village, received ROR for both homestead as and arable land.

As a result, Jaising can concentrate on cultivating land on the planes and no longer practices shifting cultivation. He is now able to grow two crops a year and is also planning to reclaim another patch of land for cultivation. As a result he has minimised his food scarcity period and is able to take better care of his children. In addition, Hari Majhi is has sufficient time to continue his studies. As Hari said,

”Aage aamar chas jami nai thibaru more bua maa donger marikari chas koru thile aaru mui makad khedikari chas ke jaguthili. Pata paiba dinu more bua donger chas besi nai karbar. Ebe more bua jamin chas ne khob dhiyan deson. More bua moke aaru donger chas jagi jiba ke nai kohebar na agar pora sabudin kosala, mandia, konda khaibake nai podbar. Dhan chas kolake bane kari khaibake be miluchhe. Aagar para ebe naina."

Earlier, my parents used to practice shifting cultivation on the hill slope as we didn’t have ROR and I used to protect the standing crop from the monkeys. After getting ROR my parents are no longer practice shifting cultivation and they are concentrating more and more on cultivating the planes. My father no longer asks me to look after the crops and are no longer confined to eating kosala (minor millet), ragi and tubers, etc. Now we are taking sufficient meal and have a better way of life.

BHIMA MAJHI

Bhima Majhi is a very simple, hard working man who about 30 years old and lives with his wife, daughter and son in Sorishbundel, a village in the Nakrudndi GP. Sorishbundel, a village in the Nakrundi GP has 15 families and is located in an inaccessible area - one has to walk around 2kms from the nearest road and climb the hills to reach it. In common with the other villagers, because Sorishbundel had not been declared a revenue village, Bhima had no homestead or arable land and he used to earn his livelihood from slash and burn cultivation and the collection of forest produce. He could earn enough from shifting cultivation to survive for 4 to 5 months of the year and collection of non-timber forest products (tubers, greens etc) helped for another 3 to 4 months but for the remaining months, Bhima as forced to take out informal loans at very high interest rates which were as high as 50%. When he was unable to repay these loans he was forced to sell his standing crops at at very low prices under the lagani system. To resolve the situation, Bhima started to encroach some patches of land in order to help his family secure enough food for the 1-2 months when he faced food stress although this rarely delivered enough food to tide him over.

As his village was not recognised as a revenue village, the revenue and forest officials used to harass Bhima and other people of his village and treated them as encroachers. When ANTODAYA intervened in Sorishbundel, people presented their problems and asked us to help them obtain Record of Rights (ROR) for the land. To achieve this, we encouraged people to raise the issue at the district as well as at the state level and to contact different officials and in 2002 Sorishbundel village was declared a revenue village status and Bhima (together with the other villages) got Record of Rights (ROR) for both homestead and arable land. ANTODAYA also extended financial support to Bhima to reclaim the streambeds for cultivation and to purchase the some agricultural implements. Now he is able to reclaim 0.85 acres of land on which he can grow second crop. In the first year he was able to harvest 7 putis (approximately 420kg) of paddy and he expects to grow 9-10 putis of paddy in following seasons.

KANA MAJHI

|

Kana Majhi, a marginal tribal farmer of Ushamaska village, lives with his wife Patta Dei and their two children. Until 2002, their village was not a revenue village and Kana Majhi, as well as all his fellow villagers, were landless and every year they had to pay a penalty to the revenue department for the land they were cultivating. |

They were termed as encroachers and the land was illegally occupied. But with ANTODAYA’s support, the villagers fought a legal battle with the State and finally won. In 2002 Ushamaska and Kirkicha both achieved revenue village status and the villagers were awarded the Record of Rights over the land they occupied.

During the same year, in order to meet some exigencies, Kana Majhi mortgaged approximately 1 acre of paddy land for Rs6000/- (six thousand), with Budu Naik of the neighbouring Mohangiri village. Due to lack of money, he was not able to release the land until March 2008. Meanwhile, under OTELP, land and water management works were executed in Ushamaska and Kana Majhi and his family members earned wages working for these projects. They saved some of their wages and with those savings to released their land from Budu Naik paying him back the Rs6000/- in full.

This kharif season, Kana Majhi has a very good paddy crop on the patch of land he had previously mortgaged and he hopes to have food security for the next 6 months. Elated, Kana Majhi and his wife told ANTODAYA:

“We were starving after mortgaging our land. We were not even able to give a good pair of clothes to our children. Now we work in our village and are getting a regular wage are able to meet those requirements – our bad times are gone. This year’s harvest from this land can feed us for six months and we shall not have to take out a loan. We shall toil hard to develop the land and not go for podu cultivation. During the summer, we got an adequate wage for work and did not go for podu this year and shall not go for podu in the coming years either.” |

SOBHA MAJHI

|

In the Sorishbundel hamlet of Ushamaska village lives Sobha Majhi, a young man of less than 30 years of age. Sobha Majhi, like other villagers of Ushamaska and Kirkicha, was landless until 2002 as their village was not a revenue village then.

Sobha Majhi and his small family were dependent upon a small patch of land they occupied and the production from podu land. Out of the production from these sources, they had food for 4-5 months a year and for the other 7-8 months they were dependent upon consumption loans. Sobha Majhi’s wife is a member of the self-help group and they had taken a loan to purchase goats and also had some NTFP trading. But when the intervention under OTELP started in their village, Sobha Majhi became the eye-opener for his fellow villagers. He became the village volunteer and set examples to others by doing innovative things himself. |

Sobha Majhi adopted all the new technologies brought to their village by ANTODAYA and OTELP. Starting from line sowing to ginger cultivation to chick pea demonstration to SRI paddy cultivation, Sobha is always ahead.In the month of April 2008, Sobha Majhi received training on SRI method paddy cultivation and experimented in his own field of approximately 1 acre. Previously he was using around 50kgs of seeds in that patch of land and the yield was around 3 quintals. But with the SRI method of cultivation, he used only 2.5 kg of seeds (Khandagiri variety) and the yield this summer was 1,078 kg. Seeing the success of Sobha Majhi, all 18 households of Sorishbundel are planning to have SRI method paddy this summer.In the Sorishbundel hamlet of Ushamaska village lives Sobha Majhi, a young man of less than 30 years of age. Sobha Majhi, like other villagers of Ushamaska and Kirkicha, was landless until 2002 as their village was not a revenue village then.

Sobha Majhi and his small family were dependent upon a small patch of land they occupied and the production from podu land. Out of the production from these sources, they had food for 4-5 months a year and for the other 7-8 months they were dependent upon consumption loans. Sobha Majhi’s wife is a member of the self-help group and they had taken a loan to purchase goats and also had some NTFP trading. But when the intervention under OTELP started in their village, Sobha Majhi became the eye-opener for his fellow villagers. He became the village volunteer and set examples to others by doing innovative things himself.

Sobha Majhi adopted all the new technologies brought to their village by ANTODAYA and OTELP. Starting from line sowing to ginger cultivation to chick pea demonstration to SRI paddy cultivation, Sobha is always ahead.

In the month of April 2008, Sobha Majhi received training on SRI method paddy cultivation and experimented in his own field of approximately 1 acre. Previously he was using around 50kgs of seeds in that patch of land and the yield was around 3 quintals. But with the SRI method of cultivation, he used only 2.5 kg of seeds (Khandagiri variety) and the yield this summer was 1,078 kg. Seeing the success of Sobha Majhi, all 18 households of Sorishbundel are planning to have SRI method paddy this summer.

PATA DEI

|

Pata Dei, a tribal girl of Turibhejiguda village under most backward Nakrundi Gram Panchayat of most deprived Thuamul Rampur Block. She is not married till date and working for the upliftment of her own community.

In the year 1994 at a tender age of 16 years, Pata Dei, the COY tribal girl joined the movement of their rights over collecting, processing and marking of Non-timber forest produces run by her elders in Banashree Mahila Sangathan. She was not literate when ANTODAYA started intervening in their village. Later on she joined the Social Education Centre (Non-formal education centre) run by ANTODAYA in their village. |

Slowly, but with commitment Pata Dei took the leadership among women not only in their village, but also at area level for ascertaining their rights over NTFP processing and marketing. After 8 long years of fighting with the faulty policy of Government the women won the battle and the rights of processing and marking of NTFPs are now with them.

Meanwhile during 1997 Pata Dei respecting the request of her elders in Banashree Mahila Sangathan, contested the Gram Panchayat election and won as the Sarpanch of Nakrundi GP. During her tenure as Sarpanch of Nakrundi GP she had encouraged her fellow women members of Banashree Mahila Sangathan to procure and process a number of NTFPs (mainly hill brooms, Amla, Mahua etc) by issuing license from Gram Panchayat. She also encouraged two of the SHGs of the Gram Panchayat to run PDS outlets.

Contribution for SHG promotion: Though Pata Dei joined Banashree Mahila Sangathan as a teen-aged member; gradually she became an active member of Maa Dokribudhi WSHG of her village and promoted so many SHGs in the nearby villages. She got the training on Kandul Dal processing and also Hill brooms processing and now she acts as a facilitator for other SHGs of the area to train them in the trade. She also promoted community shops run by SHGs in 4 villages of the area. As a Sarpanch (from 1997 to 2001) Pata Dei encouraged her fellow members to procure NTFPs and run PDS centre.

Contribution to Social reforms: As an active member of Banashree Mahila Sangathan, Pata Dei is instrumental in so many social reforms in their village as well as in the area for example:

- She organized her group members to ban illicit liquor brewing as well as vending in the area

- She encouraged the girls in her village to go to school and as a result 13 girls from her village are going to school presently.

- Through the SHG they have succeeded in eradicating the exploitation of moneylenders (Sahukars)

- Apart from SHG, they have formed one Village development revolving fund out of collection from the wages and from ANTODAYA support where there is an amount of Rs. 1,11,810/- (One lakh eleven thousand eight hundred ten) got revolved at present.

- They have a grain bank in their village to support the needy families at the time of distress.

Now after OTELP started the work in her area, Patta Dei became the village volunteer and encouraged people to work for their own resource development. Recently she got the opportunity to become the GRAM SATHI under NREGA. To make herself more capable she learnt to ride a bicycle which she purchased out of her wage money and oversees the work under NREGA and encourages social audits in every village. |

Next Page >>

<< Previous

SHIFTING PODU CULTIVATION REDUCTION

Not only is slash and burn cultivation less remunerative, it is destructive to the environment and to the agriculture lands lying below the hill. ANTODAYA planned to generate workdays under the Land and Water Management component of OTELP and discussed it with all the villages of its target area. Citing the example of the massive devastation during the last monsoon (June to September 2007) the discussion spread in all the villages. The sand and stone casting over paddy land due to the land slide during June July had brought devastation to most families some of whom had lost their entire crop. People in the target villages decided to take up two activities, namely:

• construction of loose boulder gully control structures on the dry streams

• construction of gullies and stone bunds on the degraded hill slopes

to arrest the soil erosion and to save their low-lying paddy fields. They also planned to construct field bunds, trenches, percolation tanks and water absorption trenches wherever possible.

To build the capacity of the:

• community mobilisers

• VDC functionaries

• village volunteers

• selective youths

on the subjects of

• land and water management

• design of LBS

• construction of stone bunds

• process of surveying the area |

|

To achieve these objectives, ANTODAYA organised field training and exposure visits. The participants were taught the basic techniques of contour demarcation through “A” frame, pipe level and measuring the area as well as the slope etc. As a result, back home, the volunteers and the community mobilisers organised the villagers to take up the large scale construction of loose boulder gully control structures and stone bunds.

In the process

• 7,090 meters of field bunds

• 500 meters of trenches

• 6037 LBSs

• 105,441m of stone bunds

were constructed during the 2nd half of the year 2007-08 generating 271,166 work days in the area averaging 260 work-days of employment per target family during the period. Apart from this there were other wage employment components such as the DI fund community centre construction and employment through convergence activities etc.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE BRINGS PROSPERITY FOR TRIBALS

Well intentioned Government programmes often fail because, besides the corruption and ineffective implementation, they do not include the skills and knowledge of the local people. However, with effective participation otherwise unimaginable results can often be produced and the Amjhola irrigation project is a classic example of such participation.

The background

Amjhola village is located 1,000m above sea level in the Nakrundi GP of Thuamul Rampur. This Paraja Kandha tribal village is surrounded by mountains and has a peculiar problem of scarcity amidst plenty. The stream which flows near the village carries huge amounts of water which was going to waste because rocks and other natural barriers meant it could not be used for irrigation. Without irrigation, the tribal villagers faced acute food shortages for nearly five months of the year (June to October) resulting in severe malnutrition and further adding to their vulnerability.

Almost a decade ago Integrated Tribal Development Agency (ITDA) arrived to construct a dam over the stream which, they claimed, would solve the village’s irrigation problems and lead to greater food security. However, when the project started, many of the villagers, including Laxman Majhi - the present ward member of the village, expressed concerns that the project would only provide water for a small number of fields as it was situated below the majority of the cultivated land. They also pointed out that the force of water at such a high point would erode the structure and undermine its longevity. However, as Laxman told us, the officials and contractors ignored their advice saying that they were the engineers and knew all there was to know about building dams. The tribal people were right and the engineers were wrong – the dam was washed away with flood water following the first rains.

The project

Food insecurity problems can be most effectively tackled by increasing agricultural production but at the start of the project only two families in Amjhola were benefiting from irrigation. They had achieved this by constructing a small stone embankment across the stream using their own indigenous knowledge and skill. However, because the structure was continually damaged by flood water, they had to spend a lot of time and effort reconstructing their diversion device.

ANTODAYA put forward the idea that food production could be improved with effective irrigation. We consulted the villagers who were keen to become involved in the project and they pointed out that water could be brought from the upper parts of the stream by digging a canal across the hill. However, as Dillip Das of ANTODAYA explained, this would be prove to be a Herculean task owing to a large rock through which the canal would have to be channelled. The villagers, however, needed little encouragement and immediately started breaking the rock and digging the canal along the contour line. The task took 15 days and ANTODAYA provided the workers with 7.5 quintals of bulgur wheat and some soya bean oil to provide additional sustenance during their endeavours. Just over two weeks later the stream was successfully diverted into the canal and, on seeing this, other villagers started to extend the canal further. Another huge rock would have to be overcome to achieve this extension and, as Laxman Majhi explained, with no other options left, the rock was blasted with the help of explosives.

The success story

As the water started flowing into the canal, the people stared to reclaim the waste lands and prepare the fields. They are now cultivating kharif and rabi paddy on these fields as well as sugar cane and maize in the village itself. In addition to increasing their food security, their endeavours enabled the creation of a peanut farm along with their other crops.

A further problem

Although the canal became a place of interest and was often visited by relatives and friends of the villagers, they still faced one further obstacle. As Bali Majhi - a local farmer - pointed out, the canal needed to be regularly maintained and cleared of heavy sediment both of which were badly affecting its water retaining capacity and in addition cracks had started to appear in the 1.5km canal. As the structure was constructed of dry stone and wooden logs, the canal was becoming very expensive for the villagers to maintain.

In 2003, Action Aid provided Rs2.5 lakhs through ANTODAYA to construct the canal out of concrete and for its ongoing maintenance. As Dilip Das of ANTODAYA explained, this further work was also carried out by the villagers themselves.

The outcome

A decade ago only two families in Amjhola (Bali Majhi and Karuna Majhi) were enjoying the benefits of irrigation. However, by listening to and respecting the knowledge of the local people as well as using their enthusiastic and effective participation, all the villagers are enjoying the benefits of an irrigation project which at one time appeared impossible.

The operational area of ANTODAYA, Thuamul Rampur block of Kalahandi district, is a malaria endemic zone. Immense poverty coupled with lack of knowledge on the basics of health and sanitation is the root cause of ill health in the area. Government infrastructures like PHC, additional PHC and ANM centers exist in the area but are few and far between. Most of the villages remain inaccessible in the monsoons and lack of trained people to look after immediate treatment during any ailment leaves no other options to the people but to turn to religious healers. This leads to more morbidity, compelling the people to take loans at a very exploitative rate of interest for treatment.

To sensitise the community about medical care to avoid the baseless practice of fetishism, to lessen financial crisis just for health securing purpose and to substantiate an alternative and affordable health care system for the community, ANTODAYA initiated a health-insurance scheme. Prior to this, a series of village level meetings were conducted out of which it was discovered that the financial security of the people during need and especially during outbreaks of various diseases would encourage the tribal people to care their health. So it was decided to initiate a scheme entitled as "Swasthyashree Yojana''. Under the facilitation of ANTODAYA, the scheme would be managed by Banashree Mahila Sangathan, a block level people's organisation. A team comprising ANTODAYA personnel and tribal women leaders from the community went on exposure visits to different parts of India and learnt about the experiences of different organisations related to the implementation and management of the health insurance scheme in their respective areas. Thereafter the modes and modalities of the "Swasthyashree Yojana'' were discussed with the target group. After receiving a positive response from people, the "Swasthyashree Yojana'' was launched on 9 December 2003 on the occasion of "Bikash Doot Mela - 2003" by Sri Dillip Kumar Mohanty OAS-I, Project Director, DRDA, Kalahandi.

Annual Premium of Swasthyashree:

The annual premium for the coverage of children age between 0 – 14 years for both male & female under Swasthyashree Yojana is Rs. 25/-, for female between 15 – 50 years of age is Rs. 50/- , for male age between 15 – 50 years is Rs. 75/- and for the persons both male & female having more than 50 years of age is Rs. 100/- per annum. In the scheme the insured people are provided with an insurance coverage card which is valid for one year. During the coverage period if a health problem occurs, the person consults with the doctor, all his/her expenditure (excluding subistence and traveling expenses) will be reimbursed on produce of the prescription and the medical bills. An insured person can claim up to Rs. 2000/- per annum.

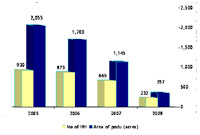

With the above facilities Swasthyashree Yojana was launched with a membership 178 persons in 2003. Now the membership coverage has increased to 997 persons covering 50 villages of 6 GPs under Thuamul Rampur block during 2006-07

During 2006/07 a total of 68 insured persons were reimbursed a total sum of Rs. 20,438/- from the scheme and this good response is leading further tribals to apply for membership is but proper knowledge on the management of this Yojana is required. With this in view, ANTODAYA has been organising a training programme on management of Swasthyashree Yojana at regular intervals for the functionaries of BMS.

PERSONAL STORIES

Hingulata Naik of Anikana

Salekram Naik and his wife, Sumani, live in Anikana village with their four children (2 daughters Hingulata and Bhumilata and two sons Chandra and Dibakar). Chandra and Dibakar have not starated school as they have not attained the proper age, but their two sister Bhumilata and Hingulata are studying in class eight and class six respectively. Hingulata was studying in the ANTODAYA run Nagavali Child Labour school up to class five but this year she entered into the higher class at Nakrundi UGME School. Hingulata's parents earn their livelihood from agriculture and seasonal business. Her mother, Sumani, is also an active member in the savings group promoted by ANTODAYA; from where she gets financial support to run her business. In 2004 Higulata's parents had enrolled the name of both Hingulata and Bhumilata in SWASTHYASHREE Yojana (health insurance scheme) and paid a yearly premium of Rs. 25/-. During August 2005 Hingulata fell ill suffering from joint pains and fever. She was admitted into the District Head Quarter Hospital at Bhawanipatna with the help of ANTODAYA and school teachers. After a week long treatment at the hospital she was cured. For her treatment her parents had to spent Rs. 1080/- which was reimbursed from SWASTHYSHREE Yojana fund.

Jugu Majhi of Swing village

Jugu Majhi is a boy of 11 years of age who resides in Swing village with his widowed mother Rukmani Dei and his elder brother Rupsingh Majhi. They have 2.5 acre of landed property and earn their livelihood by cultivating these lands and earning wages. Jugu's mother also gets widow’s pension of Rs. 100/- per month. Now Jugu Majhi is a student in class 3 at Nagavali Child Labour School run by ANTODAYA with the support from Ministry of Labour & Employment, GoI. Jugu Majhi was suffering from chronic malaria and for his treatment his family members were compelled to take out frequent loans. During the year 2005 Jugu Majhi was enrolled in the SWASTHYASHREE Yojana and because he was getting financial help from the scheme, his was able to get regular check-ups and treatment. He is now much better and is studying well. In addition, his family is no longer in a debt trap.

Gobinda Majhi of Kardapadar village

Gobinda Majhi is the eldest child of Ricksha Majhi and Biri Dei living in Kardapadar of Karlapat GP. The other two children are Shanti Dei (daughter) and Ratan Singh Majhi (son). 11 years old Gobinda studies in class III. Their family was landless before intervention of ANTODAYA in their village during 1997. With support from ANTODAYA Gobinda's father has developed one acre of land and purchased a pair of bullocks. Though they have raised their income levels, they still face scarcity during any emergencies like health hazards. Ricksha Majhi and his wife Biri Dei work hard for their children and enrolled them in SWATHYASHREE Yojana during 2004 and continue to pay annual premium of Rs. 25/- per child regularly. During October 2005 Gobinda fell ill with severe malaria. He had to be shifted to District Hospital for treatment. For his treatment SWASTHYASHREE Yojana contributed Rs. 274/- and Gobinda is OK now.

Karla Majhi of Semelpadar village

There are 41 families in Semelpadar village of Karlapat GP. Buda Majhi lives with his family wife, Wanang Dei, his son, Karla Majhi, and 4 younger children. His is one of the poorest families in the village. They earn their livelihood from 2.5 acres of land developed with the support of ANTODAYA. They also have 12 goats and poultry for additional income. 13 year old Karla Majhi studies in class seven at Tribal Welfare High School Gunupur staying in the hostel. His father had to face financial shortage for the treatment of the family. Now Karla Majhi got enrolled in SWASTHYASHREE Yojana and getting regular support for treatment.